Tipping Points: Cooperatives and the Path to Sustainable Prosperity

We have the opportunity to catalyze transformative change

19 November 2025

On October 27, SSG Principle Consultant Yuill Herbert gave the keynote address at the 2025 Global Innovation Coop Summit. The following is the full text of his remarks.

Fellow cooperators and citizens of the Earth,

Today I will talk about tipping points, cooperatives and the path to sustainable prosperity.

Today, we stand at a precipice. Not a metaphorical one, but a tangible, undeniable threshold that is existential not only for future generations, but also for people today.

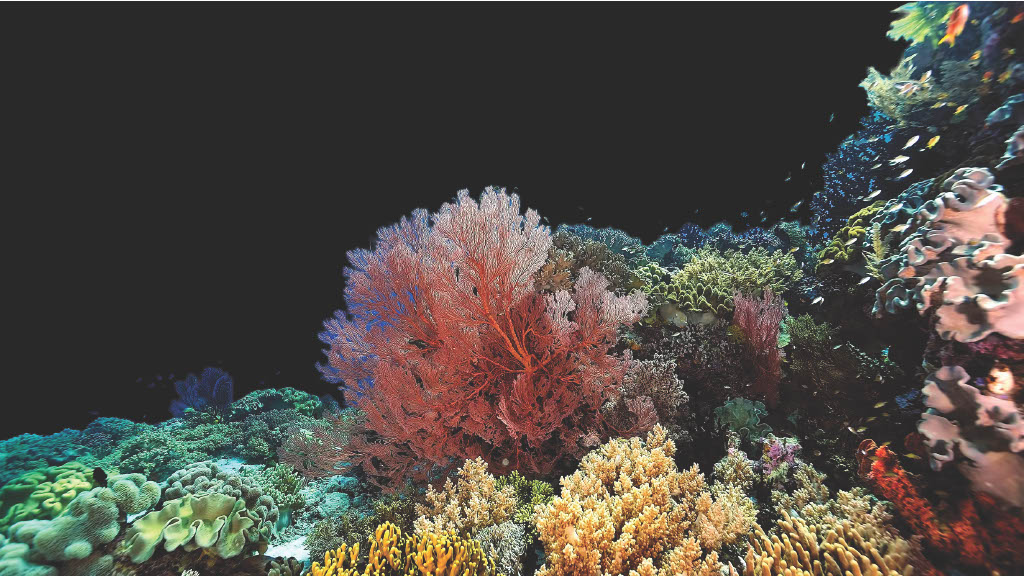

The headline in Nature two weeks ago was “Coral die-off marks Earth’s first climate ‘tipping point,’ scientists say.”

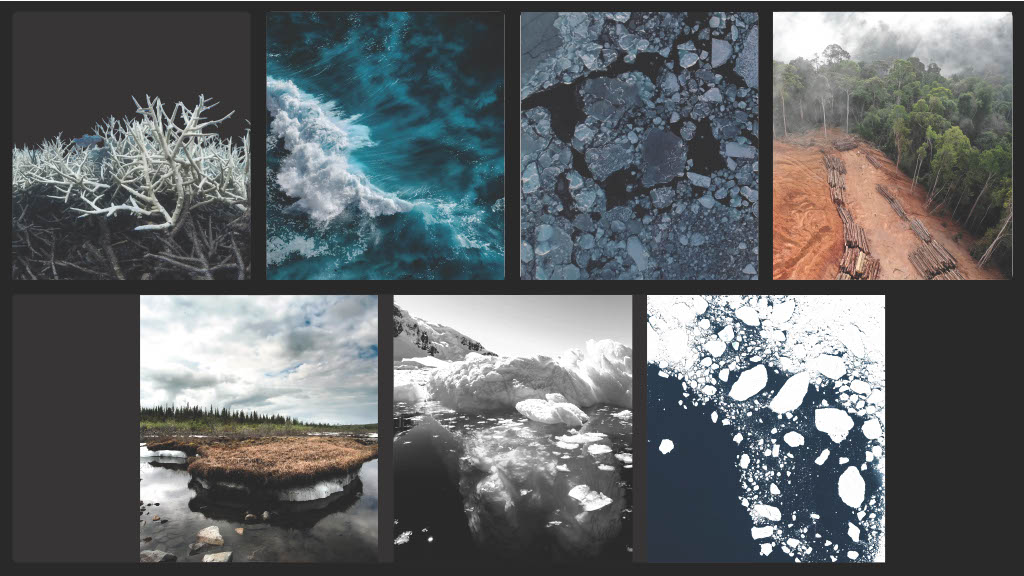

Coral reefs are one of seven global tipping points that more than 160 scientists track in the Global Tipping Points report. The 2025 version of this report begins:

The world has entered a new reality. Global warming will soon exceed 1.5°C. This puts humanity in the danger zone where multiple climate tipping points pose catastrophic risks to billions of people. Already warm-water coral reefs are crossing their thermal tipping point and experiencing unprecedented dieback, threatening the livelihoods of hundreds of millions who depend on them. Polar ice sheets are approaching tipping points, committing the world to several metres of irreversible sea-level rise that will affect hundreds of millions.

Every fraction of additional warming increases the risk of triggering further damaging tipping points. These include a collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation that would radically undermine global food and water security and plunge northwest Europe into prolonged severe winters. Together, climate change and deforestation put the Amazon rainforest at risk of widespread dieback below 2°C global warming, threatening incalculable damage to biodiversity and impacting over 100 million people who depend on the forest.”

These tipping points are not distant possibilities. They are unfolding in real time, causing economic disruption, refugee and immigrant flows, and even wars.

And so today, we stand at a precipice. Not a metaphorical one, but a tangible, undeniable threshold that is existential not only for future generations, but also for people today. Everywhere in the world. Particularly for those who are most marginalized, who have the least access to resources, and who have made little or no contribution to climate change.

I saw this first hand when I travelled to the home of the Dene people in northern Canada.

The Dene live downstream from one of the most polluting sites in the world, a vast industrial complex known as the oil sands. Equally vast tailing ponds left from the mining leak toxic chemicals into the Athabasca River, likely contributing to the elevated rates of cancer and mortality amongst the Dene people downstream.

The purpose of my visit, however, was to assess the impact of climate change on the community. Fort Chipewyan is located on one of the world’s great river deltas, where the Athabasca River flows toward the Arctic Ocean; it’s a hauntingly beautiful landscape of seemingly endless wetlands, lakes and rivers. A remote, fly-in community, the primary means of transportation for the Dene people is the river and waterways. In recent years, these routes have become impassable due to a sustained drought. A massive wildfire in 2023 forced the community from their homes, with the combination of smoke and low water levels necessitating a dramatic airlift by the military. These are the acute impacts, but it’s the chronic impacts that are perhaps more disturbing. The Dene have maintained a sophisticated ecological monitoring program for over a decade. They have tracked the disappearance of the muskrat, a key food source once abundant. The disappearance of the whitefish, also a primary food source. The disappearance of river insects. And of birds. The manager of the monitoring program told me, “The delta has gone quiet, like there is no life.” This observation echoed the famous book that gave birth to the environmental movement in the US by the scientist Rachel Carson. Its title is Silent Spring.

I heard how the loss of the ability to harvest food using traditional practices leads to the loss of language and culture, leaving young people adrift. This is not just ecological collapse—it is injustice. A stark reminder of how the forces destabilizing our climate also destabilize our societies—concentrating carbon and capital in the hands of a few, while dispersing risk across the many.

The Dene have maintained a sophisticated ecological monitoring program for over a decade. The manager of the monitoring program told me, “The delta has gone quiet, like there is no life.”

I heard how the loss of the ability to harvest food using traditional practices leads to the loss of language and culture, leaving young people adrift. This is not just ecological collapse—it is injustice. A stark reminder of how the forces destabilizing our climate also destabilize our societies—concentrating carbon and capital in the hands of a few, while dispersing risk across the many.

Social and economic tipping points are emerging.

In the midst of these challenges, there are rays of hope. Social and economic tipping points are emerging.

Mostly these are technological; in the last ten years I have watched wind turbines emerge from the hills around my house. Solar panels now cover the roofs of many homes in my region (northern climate); the cost of solar energy has plummeted by over 80% in the past decade, making it more affordable than ever before; It is now the cheapest source of electricity, displacing coal, and even natural gas in many parts of the world. Electric vehicle adoption is accelerating, with sales doubling every few years in many regions.

This year also brought a legal tipping point. A campaign led by 27 students from the University of the South Pacific culminated in a landmark legal opinion by the International Court of Justice. The Court described climate change as an “urgent and existential threat of planetary proportions.” The 15 judges concluded unanimously that the production and consumption of fossil fuels “may constitute an internationally wrongful act attributable to a state.” The finding sets the stage for lawsuits against countries and businesses that fail to protect the climate, or facilitate fossil fuel production.

These tipping points provide hope for a future beyond fossil fuels, but how we get to that future matters.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were intended to provide a roadmap for a more just, equitable, and sustainable world; they were our path.

The SDGs encompass a broad range of objectives—from eradicating poverty to combating climate change to promoting peace and justice.

The SDGs trace their lineage back to the Brundtland Commission of 1986, which sought to reconcile the economic development necessary to address global poverty with the need to respond to environmental protection. The commission’s report, which was titled “Our Common Future, brought forward the idea of “sustainable development” which it defined as meeting the “needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.”

Now, in 2025, it is a good time to ask: is this roadmap working? Are we truly meeting the needs of people today without sacrificing the future? The answer is unequivocally no. We see wildfires raging across continents, extreme heat causing death even in northern climates, agricultural systems under strain or failing, and, as I saw on my trip to the Athabasca River, ecological collapse.

These ecological crises have cascading consequences—they are uprooting people, fueling migration, and, in turn, stoking xenophobia and anti-immigrant politics, driving conflicts and wars.

Now, in 2025, it is a good time to ask: is this roadmap working? The answer is unequivocally no.

The very pursuit of growth is destabilizing or even destroying the ecological systems that make life possible.

The SDGs sought to reconcile growth with sustainability. But growth itself has become the problem.

Modern capitalism depends on constant growth to remain stable. Yet the very pursuit of growth is destabilizing or even destroying the ecological systems that make life possible. We are caught in a growth trap: endless expansion is unsustainable, halting growth risks collapse.

Why, specifically, does halting growth risk collapse? If the economy ceases to expand, increases in labour productivity will drive up unemployment and spending power will fall, along with consumer confidence.

As incomes fall, investment and tax revenues decline. Governments must then borrow not just to maintain public spending but also to stimulate demand. As the national debt increases, interest takes up a larger proportion of the national income. If the economy and, consequently, tax revenues decline for a prolonged period, funds available for public service can decline geometrically.

How has growth been sustained? By mining the commons; the public goods for private profit, in what can only be called vampire economics.

This brings us to a critical question: Is there another way?

Can we achieve prosperity without perpetual economic growth? E.F. Schumacher, in his seminal work Small Is Beautiful, argued that infinite growth on a finite planet is an impossibility. He advocated for an economy that prioritizes human well-being over material accumulation, that values quality over quantity, and that recognizes the limits of our natural resources.

To realize that vision, we must do more than tweak markets. We must change the very structure of enterprise and ownership.

Part of the problem with economic growth is to be found in the modern structures of corporate governance. The theory is that in a well-functioning free market economy, goods, services, labour and capital are freely traded. Governments intervene in markets to ensure basic rights are respected, to prevent monopolies from abusing market power, and to protect public goods. Firms are expected to maximize profits and returns to shareholders.

We must change the very structure of enterprise and ownership.

The profit-motivated firm is unlikely to be an appropriate organizational structure in an economy which is not built on growth.

But this doesn’t work.

First, it ensures that firms seek economic growth at the expense of community wellbeing, ignoring our moral obligations to one another and the common good.

Second, the model pits enterprises against the state, and states are struggling, or failing to ensure that rules are respected, rights are protected, monopolies do not abuse power, and public goods are safeguarded.

Thirdly, capital—and therefore power — concentrates among the few, shaping policy and economic thought to protect itself.

Fourthly, this system generates and promotes the myth that maximizing self interest in a situation of unequal power, resources and opportunity leads to optimal outcomes. As a result of the myth, firms can rationalize away harms to real people, communities, and nature.

The profit-motivated firm is unlikely to be an appropriate organizational structure in an economy which is not built on growth. But there is an alternative. And it already exists.

There is an alternative. And it already exists.

My involvement with cooperatives has provided me with insight and evidence that cooperatives, as an organizational model, are well-suited to providing societal needs in Schumacher’s vision.

How?

Co-operatives often (but not always) take into account broader concerns than profit alone.

The democratic ownership of co-operatives may reduce the tension between capital and the state.

Co-operatives are less likely to perpetuate consumerism as they serve needs rather than growth.

It is implausible to envision co-operatives furthering the billionaire class; cooperatives are not a means to accumulate private wealth.

But if cooperatives are so compelling a prescription, why are there not more cooperatives?

But if cooperatives are so compelling a prescription, why are there not more cooperatives?

According to the laws of Newtonian physics, apparently, the bumblebee cannot fly- its wingspan is insufficient to support its body. But bumblebees do, in fact, fly.

Why are cooperatives not at the heart of every public policy agenda of any well-meaning and informed politician?

There are likely many answers to this question. But one I find compelling, and I quote Professor Zamagni:

“According to the laws of Newtonian physics, apparently, the bumblebee cannot fly—its wingspan is insufficient to support its body weight. Yet bumblebees do, in fact, fly. In the same way, for conventional economy theory, the cooperative cannot function in the long run because its non-economic purposes are seen as a stumbling block to the attainment of the economic ones.”

Cooperatives, of course, do, in fact, function in the long run. But with this logic they are designated as outsiders, lacking not only the prerequisite self-interest but also the seductive trappings of a flashy billionaire class, private jets, venture capitalists, and unicorn investments. Cooperatives are out of tune with the quintessential American mythology of our times, or in Gramscian terms, hegemony.

The response to a hegemony must be a counter hegemony.

The World Social Forum as a counterpoint to the World Economic Forum. The Frog as satire to counter the immigration tactics in the US. Cooperatives as the antithesis of billionaires. For cooperatives are a profound symbol of possibility, that prosperity can be decoupled from consumption, that wealth can be measured in well-being and that communities can thrive while living within ecological limits.

It was with the importance of symbols in mind that I elected to pursue the cooperative model as the vessel for my life’s work. My aim was to create a form of business that demonstrated that there is another way, and in this journey I have discovered many, many others on a similar path.

Cooperatives have always emerged out of need, shaped by activists, workers, scholars, and people.

Cooperatives are a profound symbol of possibility, that prosperity can be decoupled from consumption, that wealth can be measured in well-being and that communities can thrive while living within ecological limits.

Will we wait for crises to dictate our choices, or will we proactively design systems that embody our highest values? Cooperatives offer a path.

Returning to the precipice of climate change, the need is great.

The question is: What will we do? Will we wait for crises to dictate our choices, or will we proactively design systems that embody our highest values? Cooperatives offer a path.

My vision is that cooperatives can be the engines of energy transition, the bulwarks against inequality, the laboratories of participatory democracy, and the incubators of ecological stewardship. However, the urgency of climate change means that we must confront two features not commonly associated with cooperatives—speed and scale.

So where do we start? In olden times, they talked about countries having oil reserves as a source of wealth. Today we know that every community, every place has energy reserves, solar energy reserves, waiting to be mobilized. I propose that the social tipping point for cooperatives in our time is to create solar energy co-ops in every community, in every country. Solar panels are the right technology—they are low cost, they are flexible in terms of where and how they can be installed on roofs, on balconies, in solar gardens, with agriculture. The cooperative model can be adapted according to the circumstance; think worker cooperative or consumer cooperative, with many flavours therein. Not only is this an opportunity to accelerate clean electricity, but it’s also an opportunity to democratize energy.

And the good news is that there are many solar co-ops out there that we can learn from, including the remarkable ResCoop network. From the solar co-ops, we can launch into the other key technologies of the energy transition—heat pumps, electric bikes and electric cars, and retrofits. Let the energy transition be democratized through cooperatives.

The stakes are immense. Climatic tipping points are at the door.

Social injustices persist. Growth-dependent economic systems remain entrenched. Yet opportunities exist. Falling renewable costs, technology adoption, and community mobilization create potential social and economic tipping points—if we act.

We must phase out fossil fuels, rethink sustainable development with well-being and resilience in mind, and embrace cooperatives as structural interventions. They are engines of local empowerment, laboratories of democracy, and symbols of a better economic future.

The Dene’s experience reminds us what is at risk. Schumacher reminds us what is possible. And cooperatives show us a path forward. Let us make the next tipping point one of courage, cooperation, and collective action.

Let us make the next tipping point one of courage, cooperation, and collective action.

Contact Us

Have questions about our services or want to know more about how we can help you?